At the beginning of this year, the German Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association had its first-ever H2 economic forum in the German capital. On Feb. 18, 2016, around 50 representatives from politics and business were invited to the Dutch embassy in Berlin to discuss green hydrogen opportunities with Germany’s federal environment minister, Barbara Hendricks. After the DWV had already organized a Parliamentary Evening at the British embassy last November (see DWV to Pave the Way for Green Hydrogen), the association – which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year – tried out a new format in 2016, with good results.

Monique van Daalen, the Dutch ambassador to Germany, and her business delegation had already met with professionals from the German hydrogen and fuel cell industry during the World of Energy Solutions in October 2015. In the spirit of good cooperation, she instantly voiced her willingness to host the new economic forum at her country’s embassy in Berlin.

In her speech, the German environment minister stressed the benefits of hydrogen for energy storage and at the same time distanced herself from pure biofuels in light of the years-long and sometimes harsh back and forth of the ILUC debate (see box). Hendricks made it very clear: “I want to get away from crops being diverted to biofuel production. I believe we need other, better fuels.”

ILUC

ILUC, also known as indirect land use change, suggests that the European biofuel policies will lead to an expansion of farming areas for regenerative resources in Europe and other countries, resulting in a global displacement of agricultural production. Attempts to restore the resource imbalance on the livestock and feed market will then lead to changes in land use – for example, overseas (e.g., tropical deforestation). Source: ufop

Open to discussion

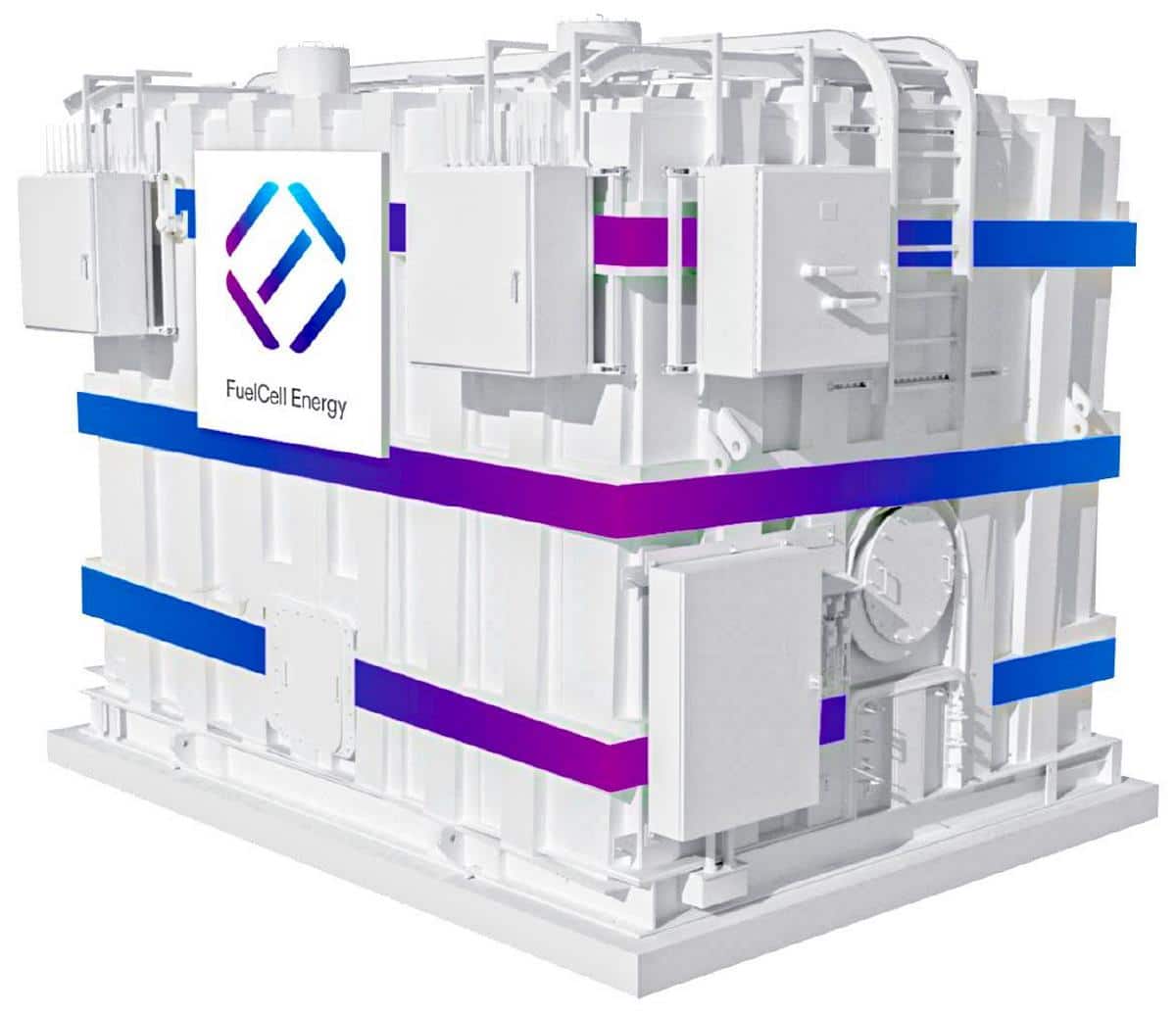

The debate that followed soon turned to current EU legislation as the key issue. For example, Ruprecht Brandis, director of external affairs at BP Europe, agreed with Hendricks’s statement that there had been “mixed experiences with biofuels over the last years” (“biofuels won’t grow into the sky”). Brandis added: “It is our aim to make green hydrogen part of the biofuel quota.” He explained that BP was pushing for the relevant legal framework and called on the Federal Environment Ministry (BMUB) and the EU Commission to support the efforts – mainly the ones that would allow the use of green hydrogen in refineries.

Tudor Constantinescu, the principal adviser to the EU Commission’s Director General in all things energy, subsequently entertained the possibility of hydrogen playing an important role in the future, especially in decarbonization, efficiency increases and development. He stressed that H2 technology had made good progress over the past years, but also acknowledged the deficits in the current regulatory framework. Nevertheless, he was highly confident that the rules could be adapted to include green hydrogen to the appropriate extent as a zero-emission fuel based on electricity.

Norbert Salomon, deputy director-general of emission control, indicated that he too was open to a debate about the rules by saying: “You don’t need to try and convince us; we are already convinced. […] There is no disagreements about content. […] We need hydrogen in refineries.” But he also voiced a note of caution, explaining that the mineral oil industry had long been in disagreement about what to make of green hydrogen use in refineries. He said: “Meanwhile, the mineral oil industry has started speaking with one voice. It wasn’t always like that.”

In principle, he confirmed that there were indeed some legal hurdles in the EU that would need to be addressed. He said: “The regulations are very clear regarding hydrogen use in refineries: None allowed.” The EU Commission would have to agree to any amendments in this case. When Constantinescu hinted that the commission was open to suggestions from EU member states (“The good will is there.”), it was Oliver Weinmann, CEO of Vattenfall Europe Innovation, who rose to speak. Summing up the preceding statements, he said that the only change that was apparently needed was a revision of a table value in the current law, but that this value could easily be changed by introducing the relevant ordinance.

This gave DWV‘s chair, Werner Diwald, hope that there would be enough time until this summer to make a concrete suggestion on how to structure the ordinance and resolve the issue before the general election in 2017.

Regulations

On Oct. 9, 2014, the German Bundestag introduced a rule that allowed the government to issue ordinances relevant to electricity-based fuels and the Federal Immission Control Act (section 37d of the BImSchG). In September 2015, the amendment of the EU directive – which grants the authority to issue ordinances – came into force. By devising a regulation as an EU member and submitting it to the EU Commission, the German federal government would be able to establish the legal framework that could allow green hydrogen use in refineries and consider it for the climate protection quota.

Green washing?

After the official part was over, one question during the numerous subsequent discussions was: What are the benefits and drawbacks of green hydrogen in refineries? Whereas some of the participants viewed it as an opportunity, a lucrative business case, others saw the risk of clean hydrogen again “green-washing” the mineral oil industry. The DWV, however, believed that the advantages outweighed the disadvantages, by “developing a business model to enable the necessary infrastructure for a long-time expansion of CO2-free transportation through fuel cell vehicles.” But some skeptics warned that only a small percentage of the hydrogen used for refining may no longer come from fossil sources (natural gas reforming). They were afraid that this small percentage could be enough for marketing departments to create a new generation of “ecological” fuels, although the benefit to the environmental would hardly be noticeable.

Netherlands

The Netherlands, which have held the EU presidency since January this year, boasts more than 90,000 electric vehicles – but also H2 buses (see photo). Much larger Germany had only 40,000 units to show for until the beginning of 2016.

DWV’s list of demands

1. The use of electricity-based fuels that are produced by renewable energy from non-biological sources (e.g., hydrogen) should be considered for the climate protection quota during fuel production – especially in the Federal Immission Control Act.

2. From 2017 on, the obligation to introduce the second generation of biofuels should explicitly include the relevant electricity-based fuels or hydrogen. The requirement of reducing GHG emissions through second-generation biofuels and power-based fuels should be at least

– 0.3% of the quota in 2018

– 0.5% of the quota in 2019

compared to the reference value of 83.8 kgCO2eq/GJ.

3. Systems for the generation of electricity-based fuels should be categorized as systems pursuant to section 64 of the Renewable Energy Act if they can supply the grid. These system should also be exempt from electricity tax and grid fees in case of grid supply.

0 Comments